In a previous post in the Rails Performance series we stated that the default garbage collection settings for Ruby on Rails applications are not optimal. In this post we’ll explore the basics of object age in RGenGC, Ruby 2.1’s new restricted generational garbage collector.

As a prerequisite of this and subsequent posts, basic understanding of a mark and sweep1 collector is assumed.

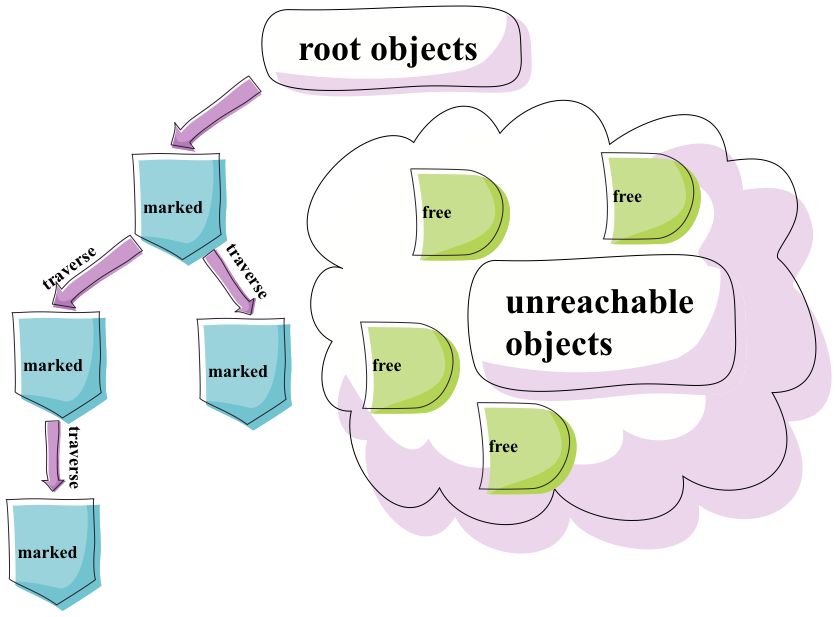

A somewhat simplified mark and sweep cycle goes like this:

- A mark and sweep collector traverses the object graph.

- It checks which objects are in use (referenced) and which ones are not.

- This is called object marking, aka. the MARK PHASE.

- All unused objects are freed, making their memory available.

- This is called sweeping, aka. the SWEEP PHASE.

- Nothing changes for used objects.

A GC cycle prior to Ruby 2.1 works like that. A typical Rails app boots with 300 000 live objects of which all need to be scanned during the MARK phase. That usually yields a smaller set to SWEEP.

A large percentage of the graph is going to be traversed over and over again but will never be reclaimed. This is not only CPU intensive during GC cycles, but also incurs memory overhead for accounting and anticipation for future growth.

Old and young objects

What generally makes an object old?

- All new objects are considered to be young.

- Old objects survived at least one GC cycle (major or minor) The collector thus reasons that the object will stick around and not become garbage quickly.

The idea behind the new generational garbage collector is this:

MOST OBJECTS DIE YOUNG.

To take advantage of this fact, the new GC classifies objects on the Ruby heap as either OLD or YOUNG. This segregation now allows the garbage collector to work with two distinct generations, with the OLD generation much less likely to yield much improvement towards recovering memory.

For a typical Rails request, some examples of old and new objects would be:

- Old: compiled routes, templates, ActiveRecord connections, cached DB column info, classes, modules etc.

- New: short lived strings within a partial, a string column value from an ActiveRecord result, a coerced DateTime instance etc.

Young objects are more likely to reference old objects than old objects referencing young objects. Old objects also frequently reference other old objects.

1 2 | |

Notice how the transient attribute keys and names reference the long lived columns here:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | |

Age segregation is also just a classification – old and young objects aren’t stored in distinct memory spaces – they’re just conceptional buckets. The generation of an object refers to the amount of GC cycles it survived:

1 2 3 4 | |

What the heck is major and minor GC?

You may have heard, read about or noticed in GC.stat output the terms “minor” and “major” GC.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | |

Minor GC (or “partial marking”): This cycle only traverses the young generation and is very fast. Based on the hypothesis that most objects die young, this GC cycle is thus the most effective at reclaiming back a large ratio of memory in proportion to objects traversed.

It runs quite often - 26 times for the GC dump of a booted Rails app above.

Major GC: Triggered by out-of-memory conditions - Ruby heap space needs to be expanded (not OOM killer! :-)) Both old and young objects are traversed and it’s thus significantly slower than a minor GC round. Generally when there’s a significant increase in old objects, a major GC would be triggered. Every major GC cycle that an object survived bumps its current generation.

It runs much less frequently - six times for the stats dump above.

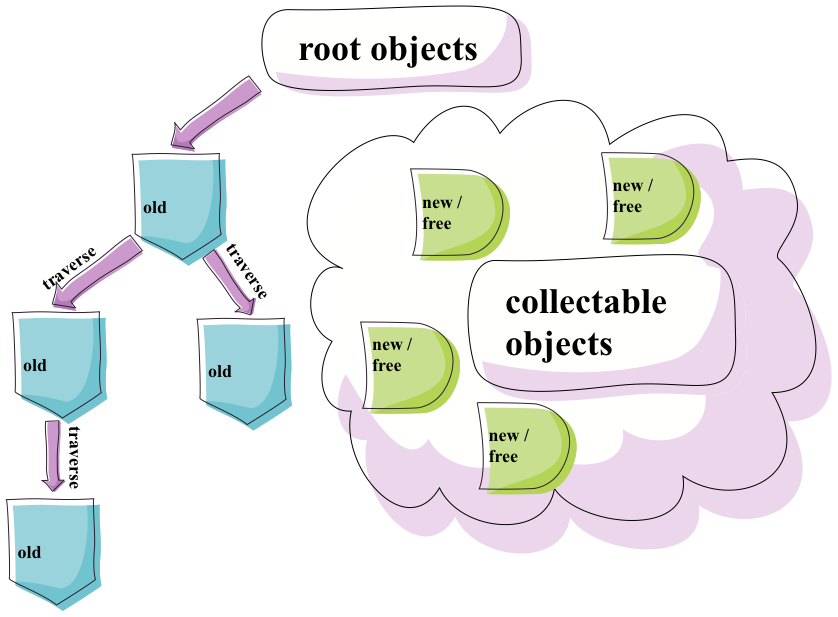

The following diagram represents a minor GC cycle (MARK phase completed, SWEEP still pending) that identifies and promotes some objects to old.

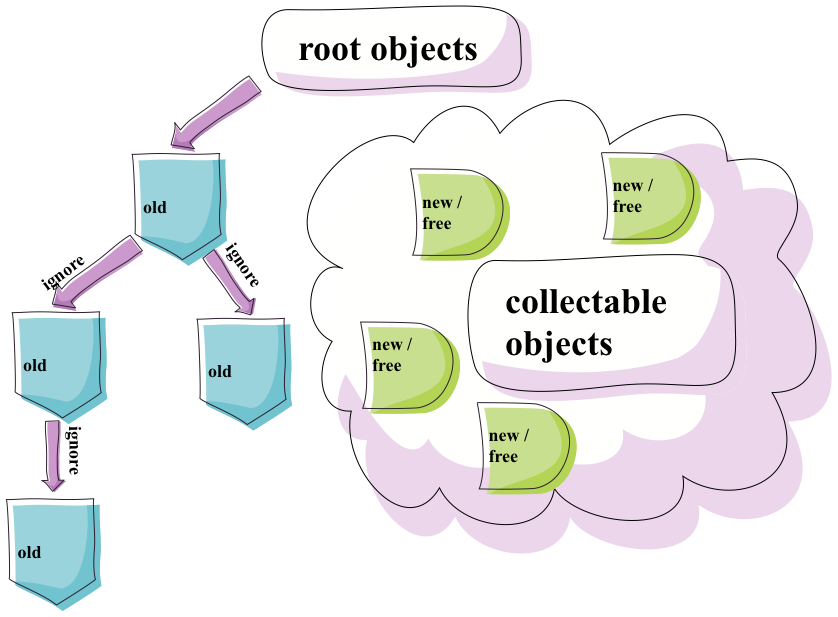

A subsequent minor GC cycle (MARK phase completed, SWEEP still pending) ignores old objects during the mark phase.

Most of the reclaiming efforts are thus focussed on the young generation (new objects). Generally 95% of objects are dead by the first GC. The current generation of an object is the number of major GC cycles it has survived.

RGenGC

At a very high level C Ruby 2.1’s collector has the following properties:

- High throughput - it can sustain a high rate of allocations / collections due to faster minor GC cycles and very rare major GC cycles.

- GC pauses are still long (“stop the world”) for major GC cycles.

- Generational collectors have much shorter mark cycles as they traverse only the young generation, most of the time.

This is a marked improvement to the C Ruby GC and serves as a base for implementing other advanced features moving forward. Ruby 2.2 supports incremental GC and object ages beyond just old and new definitions. A major GC cycle in 2.1 still runs in a “stop the world” manner, whereas a more involved incremental implementation (Ruby 2.2) interleaves short steps of mark and sweep cycles between other VM operations.

Object references

In this simple example below we create a String array with three elements.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Very much like a river flowing downstream, the array has knowledge of (a reference to) each of its String elements. On the contrary, the strings don’t have an awareness of (or references back to) the array container.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

We stated earlier that:

Young objects are more likely to reference old objects, than old objects referencing young objects. Old objects also frequently reference other old objects.

However it’s possible for old objects to reference new objects. What happens when old objects reference new ones?

Old objects with references to new objects are stored in a “remembered set”. The remembered set is a container of references from old objects to new objects and is a shortcut for preventing heap scans for finding such references.

Implications for Rails

As our friend Ezra used to say, “no code is faster than no code.” The same applies to automatic memory management. Every object allocation also has a variable recycle cost. Allocation generally is low overhead as it happens once, except for the use case where there are no free object slots on the Ruby heap and a major GC is triggered as a result.

A major drawback of this limited segregation of OLD vs YOUNG is that many transient objects are in fact promoted to old during large contexts such as a Rails request. These long lived objects eventually become unexpected “memory leaks”. These transient objects can be conceptually classified as of “medium lifetime” as they need to stick around for the duration of a request. There’s however a large probability that a minor GC would run during request lifetime, promoting young objects to old, effectively increasing their lifetime to well beyond the end of a request. This situation can only be revisited during a major GC which runs infrequently and sweeps both old and young objects.

Each generation can be specifically tweaked, with the older generation being particularly important for balancing total process memory use with maintaining a minimal transient object set (young ones) per request. And subsequent too fast promotion from young to old generation.

In our next post we will explore how you’d approach tuning the Ruby GC for Rails applications, balancing tradeoffs of speed and memory. Leave your email address below and we’ll let you know as soon as it’s posted.

-

See the Ruby Hacking Guide’s GC chapter for further context and nitty gritty details. I’d recommended scanning the content below the first few headings, until turned off by C.↩

Metal

Metal