This is the transcript of the talk I gave in Reaktor Dev Day in Helsinki, September 26, 2014.

Thanks, and hi, everyone! It’s a real honor to be here. I’ve been a big fan of Reaktor for a long time, that is, UNTIL ALL MY GEEK FRIENDS DEFECTED THERE. There’s been lots of talk about Rosatom building a new nuclear plant here in Finland. I say fuck that, we already have enough nuclear knowledge locally. But I digress.

I’d like to be one of the cool kids and Start with Why just like Simon Sinek told us. However, before that it’s worth defining the term metaprogramming in the context of this talk.

What do we mean by metaprogramming? In its simplest form, metaprogramming means code that writes code.

A-ha! So, code generators are metaprogramming, too? Not really. I go with the definition where the code is generated on the fly in the runtime. We could perhaps call it dynamic metaprogramming. This means that most of what I’m going to talk about is not possible in a static language.

So a more appropriate definition might be, to quote Paolo Perrotta,

Writing code that manipulates language constructs at runtime.

Why?

But why, I hear you ask. What’s in it for me? Well, first of all, because metaprogramming is…

…magic. And magic is good, right? Right? RIGHT? Well, it can be. At least it’s cool.

It’s also a fun topic for a conference like this, because it’s frankly, quite often, mind-boggling. Think of it like this. You take your brain out of your head. You put it in your backpocket. Then you sit on it. Does it bend? If it does, you’re talking about metaprogramming.

I also like things that make me scratch my head. I mean, scratching your head is a form of exercise. Just try it yourself. Scratch your head vigorously and your Fitbit will tell you you worked out like crazy today. That’s healthy.

But all joking aside, we don’t use metaprogramming to be clever, we use it to be flexible. And with Ruby – and any other sufficiently dynamic language – in the end of the day, metaprogramming is just a fancy word for normal, advanced programming.

Why Ruby?

So why Ruby? First of all, Ruby is the language I know by far the best. Second, Ruby combines Lisp-like dynamism and flexibility to a syntax that humans can actually decipher.

Like said, in Ruby there’s really no distinction between metaprogramming and advanced OO programming in general. Thus, before we go to things that are more literally metaprogramming, let’s have a look at Ruby’s object model and constructs that lay the groundwork for metaprogramming.

Thus, in a way, this talk can be reduced to advanced OO concepts in Ruby.

How?

Before we delve more deeply into the Ruby object model, let’s take a step back and have a look at what we mean by object-orientation.

Generally, there are two main approaches to object-oriented programming. By far the most popular is class-based OO, used in languages such as C++ and Java. The other one is prototype-based OO, which is most commonly seen in Javascript. So which of the two does Ruby use?

Class-based? Well, let’s have a look.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

How’s that for prototype-oriented OO in Ruby? But, noone does anything like this with Ruby. No? Just ask the DCI guys. Or, well, ask Gary about DCI (and Snuggies).

But I get your point, mainly when you do Ruby programming, you use something that resembles more the good ole class-based OO model. However, in Ruby it comes with a twist – or a dozen.

Everything is executable

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

In Ruby, everything is executable, even the class definitions. But it doesn’t end there. What does the following produce?

1 2 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

Event? Let’s see.

1 2 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Bet you didn’t see that coming. Ok, I’ll admit, I hid something out of the original listing.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Remember, everything is executable. Thus, this would be just as valid:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Stupid? Yes, but valid nonetheless.

Open classes

In Ruby, you can open any class, even the built-in classes, to modify it. This is something that is called monkey-patching, or duck punching for extra giggles.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Everything is an Object

Even methods. Thus you can even do functional style programming with Ruby. Think about it, you can use your favorite language to cook a delicious meal of callback spaghetti. Believe me, I’ve tried.

1 2 | |

Classes are Objects, too

Wait, what?

But, classes are different, I hear you say. They have class methods, and stuff.

I’ll let you into a secret. In Ruby, class methods are just like Ukraine in docent Bäckman’s rethoric: they don’t really exist. Wanna proof?

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Here’s an example of a class method in Ruby. Self is the current object, which in the case of a class definition is the class itself. Does this look familiar?

It should.

Singleton Methods

1 2 3 | |

Singleton methods are methods that are defined for a single object, not for the whole object class.

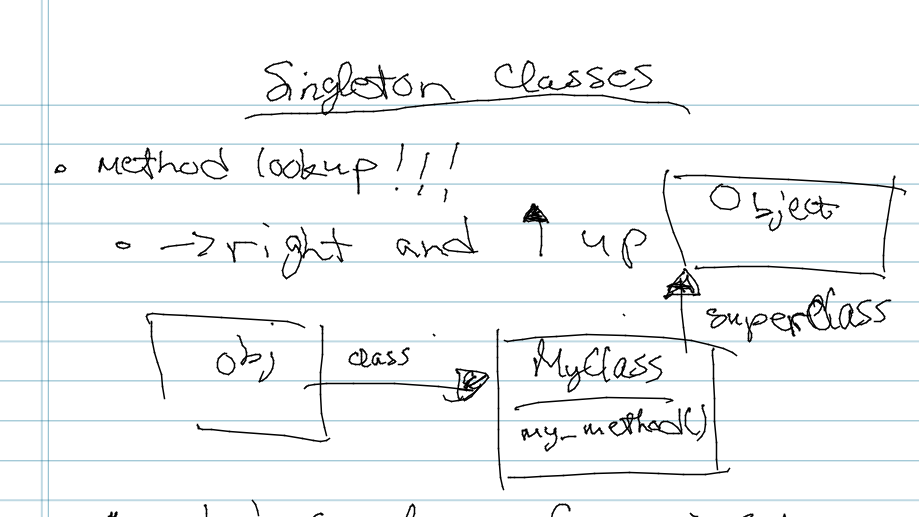

Ruby method lookup

Above is a simple (and pretty, huh?) diagram of Ruby method lookup. Methods reside in the object’s class, right of the object in the image. But where do singleton methods live? They can’t sit in the class, since then they’d be shared by all the objects of the same class. Neither can they be in the Object class, for the same reason.

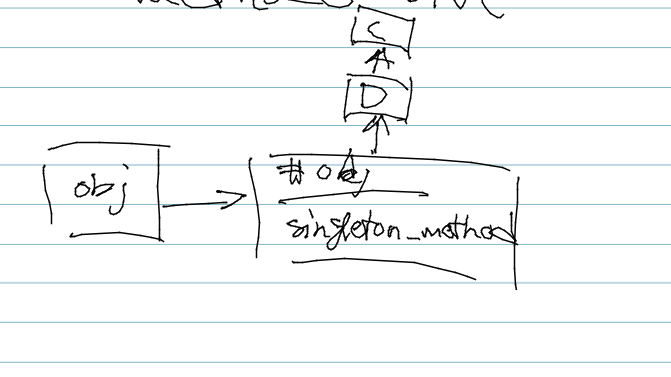

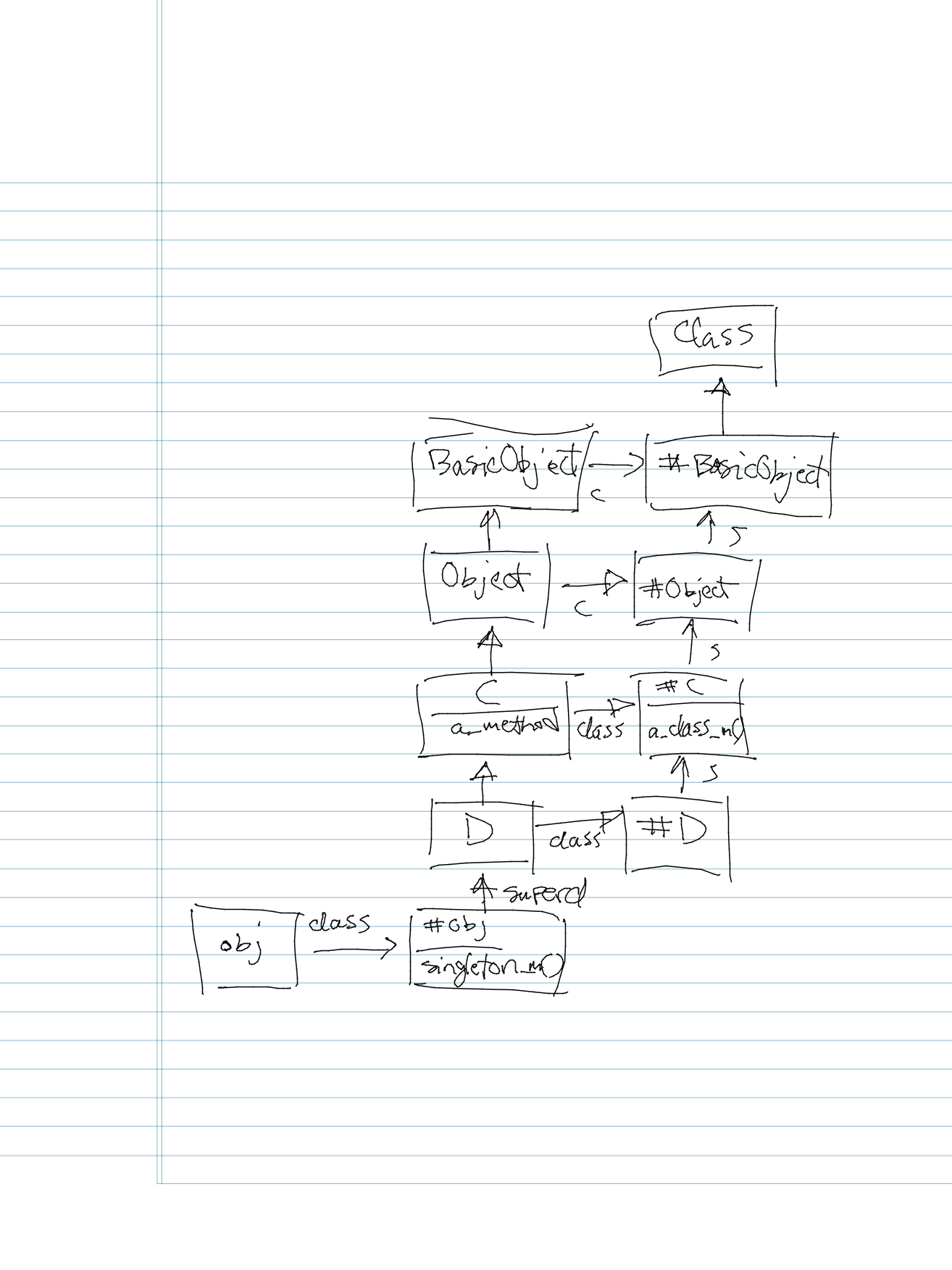

Turns out they live in something called a singleton class.

Singleton class

Singleton class, a.k.a ghost class, metaclass, or eigenclass, is a special case of a class. It’s a regular class except for a couple of details:

- It’s hidden from the generic class hierarchy. Thus e.g. the

#ancestorsmethod for a class never lists singleton classes. - It cannot be directly inherited.

- It only ever has a single instance.

So, what are class methods? They’re simply singleton methods for the class object itself. And like all singleton methods, they live in the singleton class of the object in question – in this case, the class object. Because classes are just objects themselves.

This has an interesting corollary. Singleton classes are classes, and classes are objects, so…

…wait for it…

…a singleton class must have its own singleton class as well.

That’s right, it’s turtles…errr…singleton classes all the way down. Is it starting to feel like metaprogramming already? We have barely started.

Generating Code Dynamically in Ruby

We’re going to have a look at four different ways to generate code dynamically in Ruby:

evalinstance_eval&class_evaldefine_methodmethod_missing

eval

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Eval is the simplest and barest way to dynamically execute code in Ruby. It takes a string of code and then executes it in the current scope. You can also give eval an explicit scope using a binding object as the second argument.

1 2 3 4 | |

Eval is super powerful, but has a few huge drawbacks:

- It messes up syntax highlighting and autocompletion since the code is just a string as far as the editor goes.

- It is a giant attack vector for code injection, unless you carefully make sure that no user-submitted data is passed to eval.

For these reasons eval has slowly fallen out of favor, but there are still some cases where you have to drop down to bear metal (excuse the pun) means. As a rule of thumb however, you should as a first option resort to one of the following constructs.

instance_eval

Put simply, instance_eval takes a block of code and executes it in the context of the receiving object. It can – just like eval – take a string, but also a real code block:

1 2 3 4 | |

For the reasons above, you should probably use a code block with instance_eval instead of a string of code, unless you know what you’re doing and have a good reason for your choice.

A very common usecase for instance_eval is to build domain-specific languages.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

class_eval

class_eval is the sister method for instance_eval. It changes the scope to inside the class definition of the used class. Thus, unlike instance_eval, it can only be called for classes and modules.

Because of this, a bit counterintuitively methods defined inside class_eval will become instance methods for that class’s objects, while methods defined inside ClassName.instance_eval will become its class methods.

1 2 3 | |

define_method

define_method is the most straightforward and highest-level way to dynamically create new methods. It is just the same as using the normal def syntax, except:

- With

define_methodyou can set the method name dynamically. - You pass a block to

define_methodas the method body.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

It is worth noting that you often use both *_eval and define_method together, e.g. when defining class methods.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

method_missing

method_missing is a special case of dynamic code in Ruby in that it doesn’t just by itself generate any dynamic code. However, you can use it to catch method calls that otherwise would go unanswered.

method_missing is called for an object when the called method is not found in either the object’s class or any of its ancestors. By default method_missing raises a NoMethodError, but you can redefine it for any class to work as you need it to.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

method_missing is an example of a hook method in Ruby. Hook methods are similar to event handlers in Javascript in that they are called whenever a certain event (such as an unanswered method call above) happens during runtime. There are a bunch of hook methods in Ruby, but we don’t have time to dive deeper into them during this talk.

method_missing differs from the previous concepts in this talk in that it doesn’t by itself generate new methods. This has two implications:

- You don’t need to know the name of potentially called methods in advance. This can be very powerful in e.g. libraries that talk to external APIs.

- You can’t introspect the methods caught by

method_missing. This means that e.g.#instance_methodswon’t return the “ghost methods” that onlymethod_missingcatches. Likewise,#respond_to?will return false regardless of whethermethod_missingwould have caught the call or not, unless you also overwrite therespond_to_missing?method to be aware of the ghost method.

Example: attr_accessor Rewritten in Ruby

To top off this talk, we’re going to combine the topics we have learned so far to do a simple exercise. Namely, we’re going to rewrite a simple Ruby language construct ourself, in pure Ruby.

Ruby has a simple construct called attr_accessor that creates getter and setter methods for named instance variables of the class’s object.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

While attr_accessor above looks like some kind of keyword, it is actually just a call to a class method1. Remember, the whole class definition is executable code and self inside the class definition is set to the class itself. Thus, the line is the same as:

1

| |

So, how to add the method to the class?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

In the code above we define a new class method, nattr_accessor2. Then we iterate over all the method names the method is called with3. For each method, we use define_method twice, to generate both the getter and setter methods. Inside them, we use the instance_variable_get and instance_variable_get methods to dynamically get and set the variable value. Using these methods we can again avoid having to evaluate a string of code, the way as with using define_method.

Let’s now take a look whether our code works:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

But what if we want to make the method more reusable? Where should it go then?

We could obviously put it into the Object class:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

But what if we don’t want it everywhere, cluttering the inheritance chain? Let’s put it in a module and reuse it where needed.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

Now we can use it our class:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Oops. What happened?

We used include to get the Nattr module into Animal. However, include will take the methods in the module and make them instance methods of the including class. However, we need the method as a class method. What to do?

Fortunately, Ruby has a similar method called extend. It works the same way as include, except that it makes the methods from the module class methods4 of our Animal class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

Now we’re talking.

Problems with metaprogramming

Lemme tell you a story. About a dozen or so years ago I was living in Zürich, as an exchange student. I hadn’t yet found a permanent apartment so I was living at some friends’ place while they were abroad. A permanent internet connection wasn’t an ubiquitous thing back then, and the Swiss aren’t big into tv’s, so I had to figure out things to do at nights. I was living alone, and as a somewhat geeky guy I wasn’t that much into social life. Thus, I mostly read at nights. I had just found this Joel guy and a shitload of his writings, so I used the printers at the university to print on the thin brownish paper (hey, it was free!) his somewhat ranting articles and then spent nights reading about camels and rubber duckies, the Joel test, – and leaky abstractions. And that is what metaprogramming in many cases is: an abstraction.

Now, there is nothing inherently wrong with abstractions – otherwise we’d all be programming in Assembler – but we’ll have to keep in mind that they always come at a cost. So keep in mind that metaprogramming is a super powerful tool to reduce duplication and to add power to your code, but you do have to pay a price for it.

Using too much metaprogramming, your code can become harder to:

- read,

- debug, and

- search for.

So use it as any powerful but potentially dangerous tool: start simply but when the complexity gets out of hand, sprinkle some metaprogramming magic dust to get back on the driver’s seat. Never use metaprogramming just for the sake of metaprogramming.

As Dave Thomas once said:

“The only thing worth worrying about when looking at code is ‘is it easy to change?’”

Keep this in mind. Will metaprogramming make your code easier to change in this particular case? If yes, go for it. If not, don’t bother.

Where now?

We’ve only had time to scratch the surface of Ruby object model and metaprogramming. It’s a fractal of sometimes mind-boggling stuff, which also makes it so interesting. If you want to take the next steps in you advanced Ruby object model and metaprogramming knowledge, I’d recommend checking out the following:

- Dave Thomas’s screencasts at Prag Prog. They’re a bit dated as in they cover Ruby 1.8. However, not that much has changed since then. Watching them also makes you feel good because you can see the great Prag Dave use Textmate, make mistakes, and delete characters in the code one by one.

- Paolo Perrotta’s Metaprogramming Ruby was just updated to cover the latest Ruby and Rails versions. It’s a very down-to-earth and easy read of a sometimes intimidating subject.

- If you already think you know everything about the subject, I’d recommend checking out Pat Shaughnessy’s Ruby Under a Microscope. It goes down to the level of how the Ruby object model is implemented in C (yeah, really), while still being an entertaining read.

- Last but not least, read the source, Luke. Any non-trivial Ruby application is bound to have more than its share of metaprogramming sprinkled into it. Because, in Ruby, metaprogramming is just programming.

-

Yeah, I know, singleton method of the class itself.↩

-

Let’s name it something other than the built-in method just to avoid name collisions and nasty surprises.↩

-

The asterisk before the parameter name means that we can have a number of arguments, each of which will be passed to the method in an array called

meths.↩ -

Technically, it opens up the singleton class of the Animal class and throws the methods in there. Thus they’ll become singleton methods for the Animal class, just like we want them to.↩

Metal

Metal